Going Clearview: Inside Charles Johnson’s Legal Battle with His Former Company

The High Price of Accepting Technology at Face Value

A few days ago, I attended a case conference in federal court in NYC with my friend Charles Johnson regarding his lawsuit against Clearview AI. He invited me to keep him company on the ride. There’s nothing quite like arriving in NYC at 3 a.m. and driving past landmarks like Radio City Music Hall, stripped of the bustling faces that usually imbues these buildings with a sense of importance.

I knew little about Charles’ lawsuit against Clearview AI, except that the company denied his role as a co-founder, he had been pushed out, and his ownership stake was reduced to 10%. For years, Charles has raised ethical concerns about how Clearview AI utilizes its facial recognition technology.

As we drove into the city, he pointed out a restaurant where the company had been conceived. He seemed forlorn.

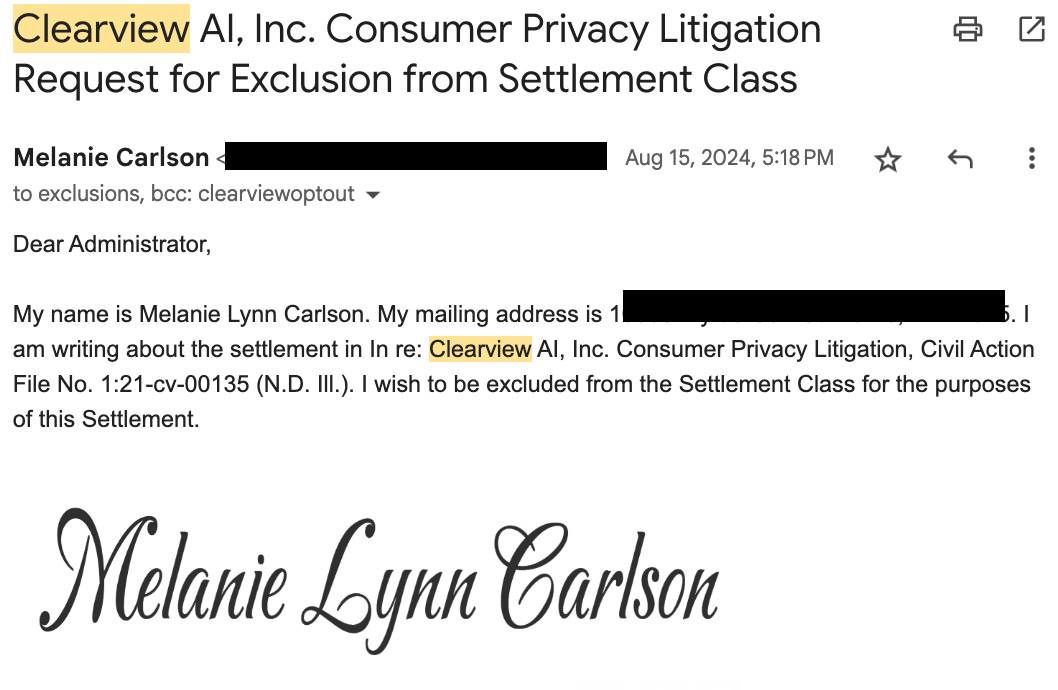

Charles and I met via Substack and Twitter. At the time, he was sharing information on why people should opt out of a settlement for a class action lawsuit against Clearview AI. It’s surprising to see a shareholder in a company worth hundreds of millions of dollars advocating for open avenues for future civil lawsuits against it—something that could significantly diminish its value.

But Charles’ reasoning was clear: the class action settlement didn’t address the core ethical issues with Clearview’s use of biometric data without consent.

Activist groups in California are urging members of a class action against Clearview AI to reject the settlement recently agreed to on grounds that it sidesteps the central issue and allows the company to continue unjust biometric data collection and use practices.

Under the settlement, plaintiffs (and their attorneys) would collectively receive a 23 percent stake in Clearview, which could be redeemed for alternative compensation under multiple scenarios. The “Renderos v. Clearview AI, Inc.” case in California is one of 12 class actions in different districts that will be consolidated by the Judicial Panel on Multidistrict Litigation if the settlement is approved…

Members of a class action who opt out can then pursue subsequent legal actions…

“By offering only monetary compensation, this settlement legitimizes Clearview’s extractive and invasive business model. It does not address the root of the problem. Clearview gets to continue its practice of harvesting and selling people’s faces without their consent, and using them to train its AI tech,” says Just Futures Law Legal Director Sejal Zota, a lead attorney in the case. “As one of the only remaining lawsuits in the country challenging Clearview’s practices, the case is more imperative than ever.” — BiometricUpdate.com, June 19, 2024

Johnson v. Clearview, et al.

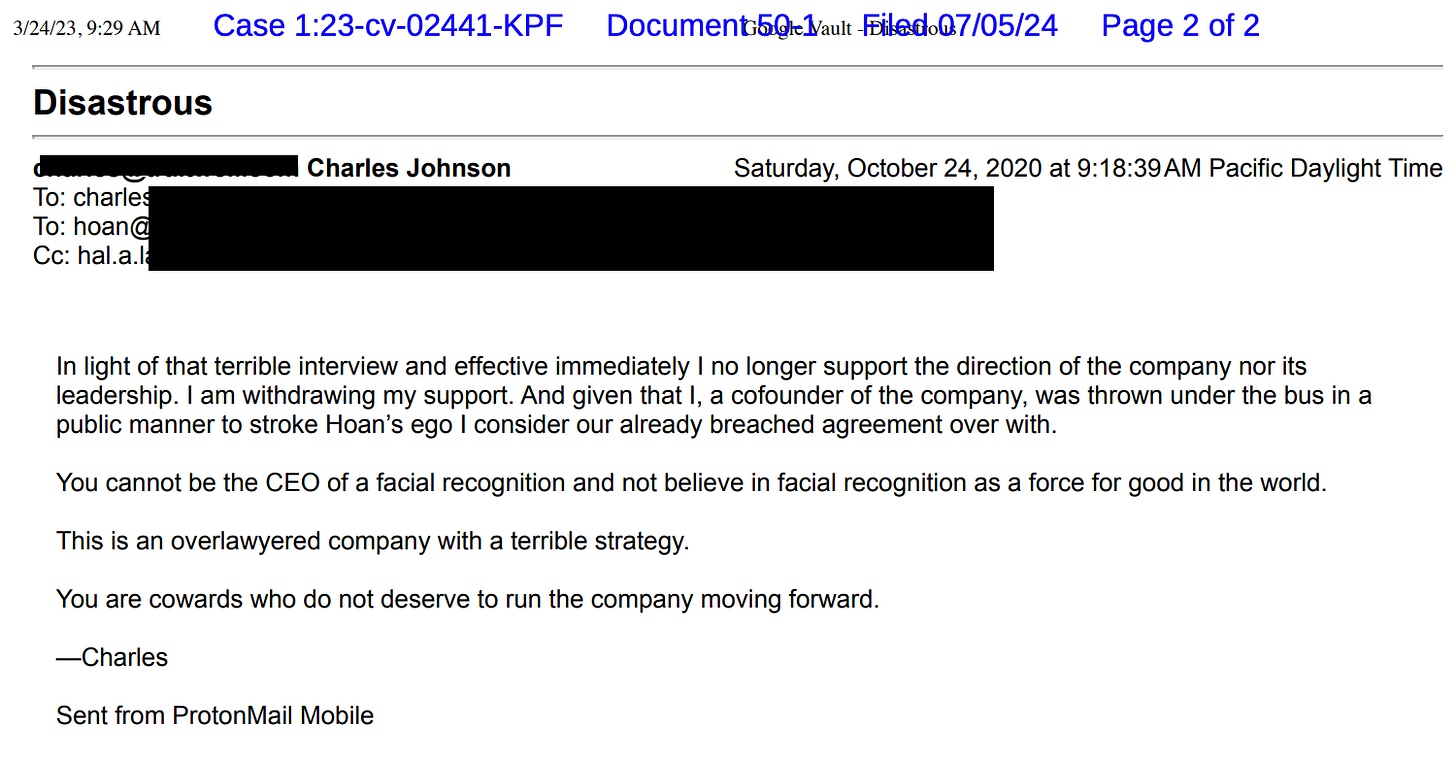

Clearview AI was co-founded in 2017 by Charles Johnson, Hoan Ton-That, and Richard Schwartz. The lawsuit, Johnson v. Clearview AI, et al., was filed March 22, 2023, centers on Charles’ ownership in the company.

The documentary Your Face Is Ours: The Dangers of Facial Recognition Software provides a succinct summary of Charles’ battles—alongside public and governmental efforts—against Clearview.

January 8th, 2024: Case Conference

Part 1: Social Media & The First Amendment

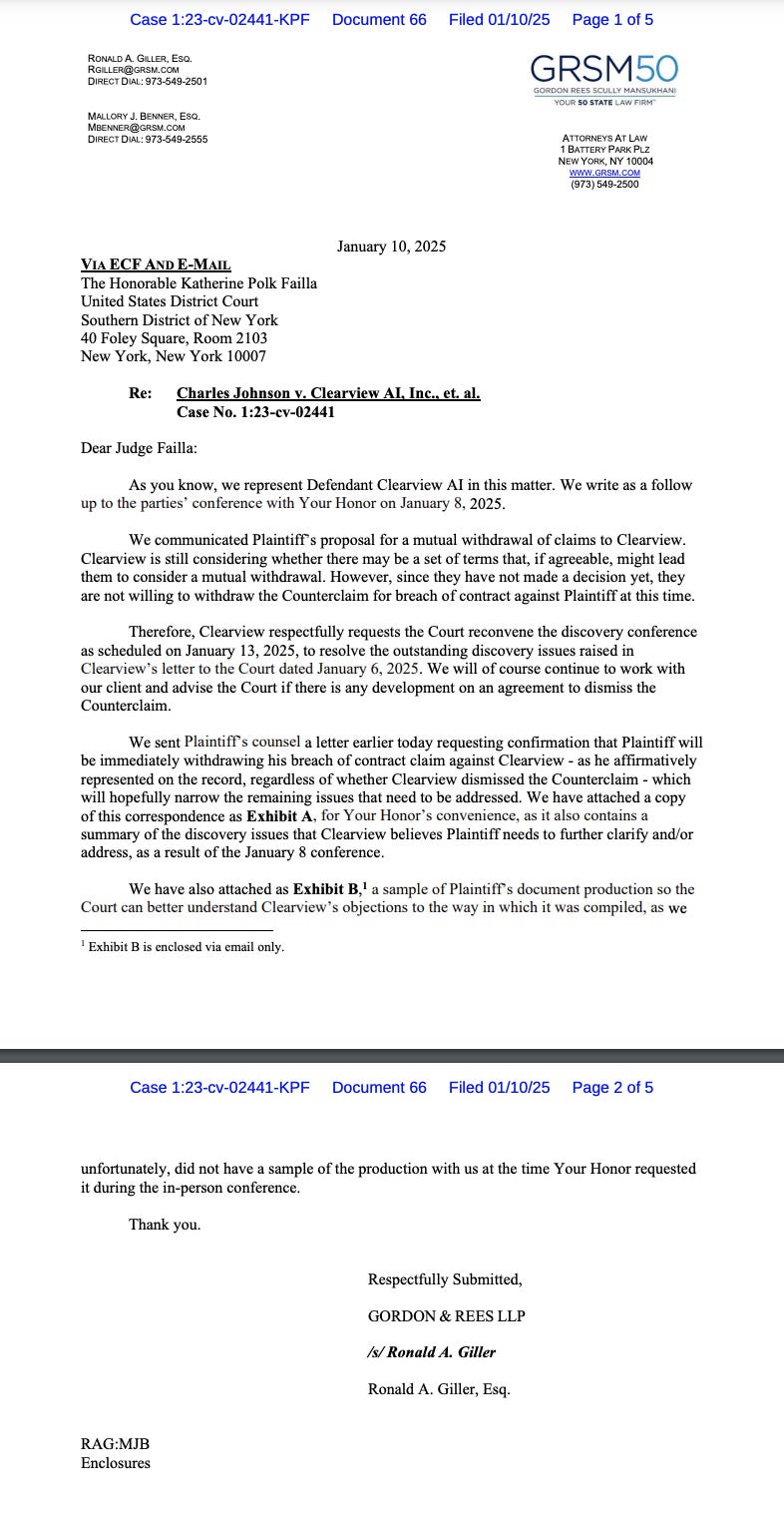

The hearing started tensely, with Judge Failla quickly addressing Charles’ social media posts, potential sanctions, and his First Amendment rights. It was no wonder Charles seemed on edge. From her perch on the bench, Judge Failla came across as sharp and methodical. It was a long hearing; I’ll link the transcript once it becomes available.

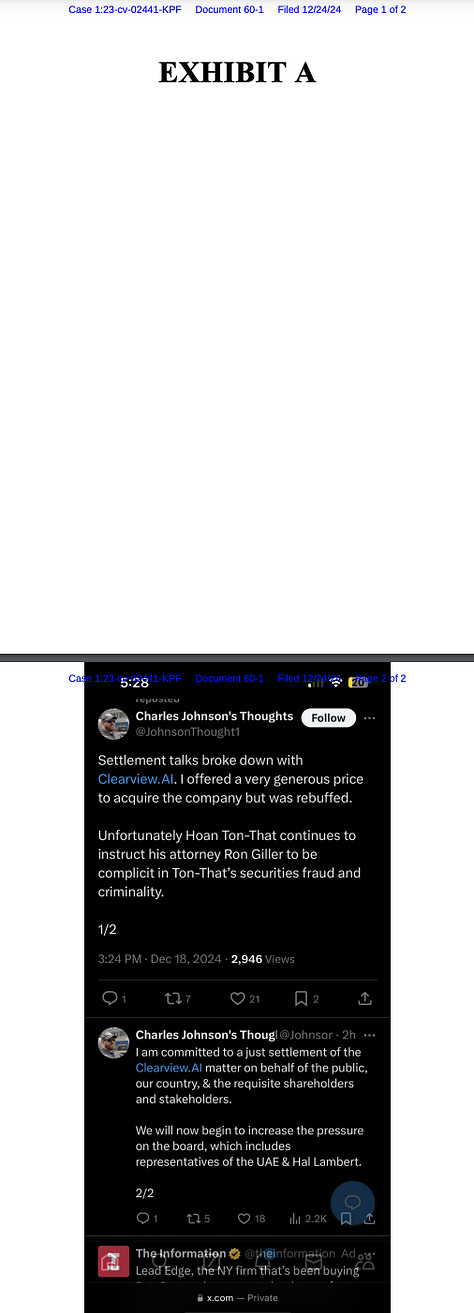

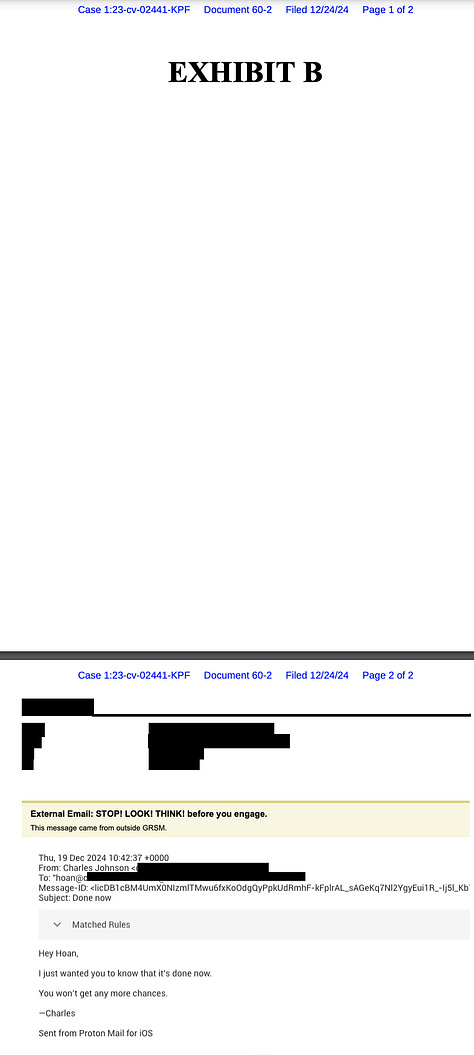

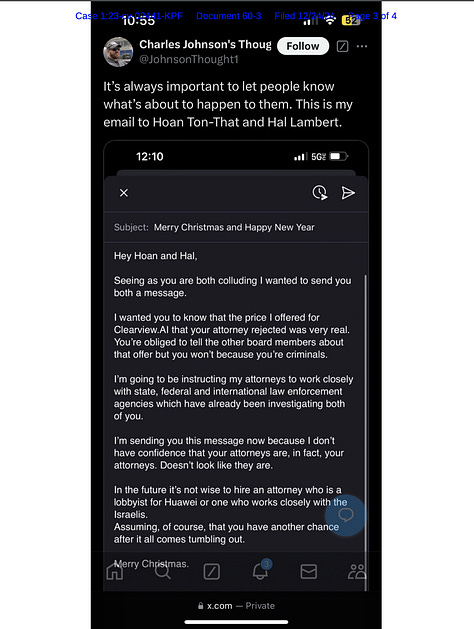

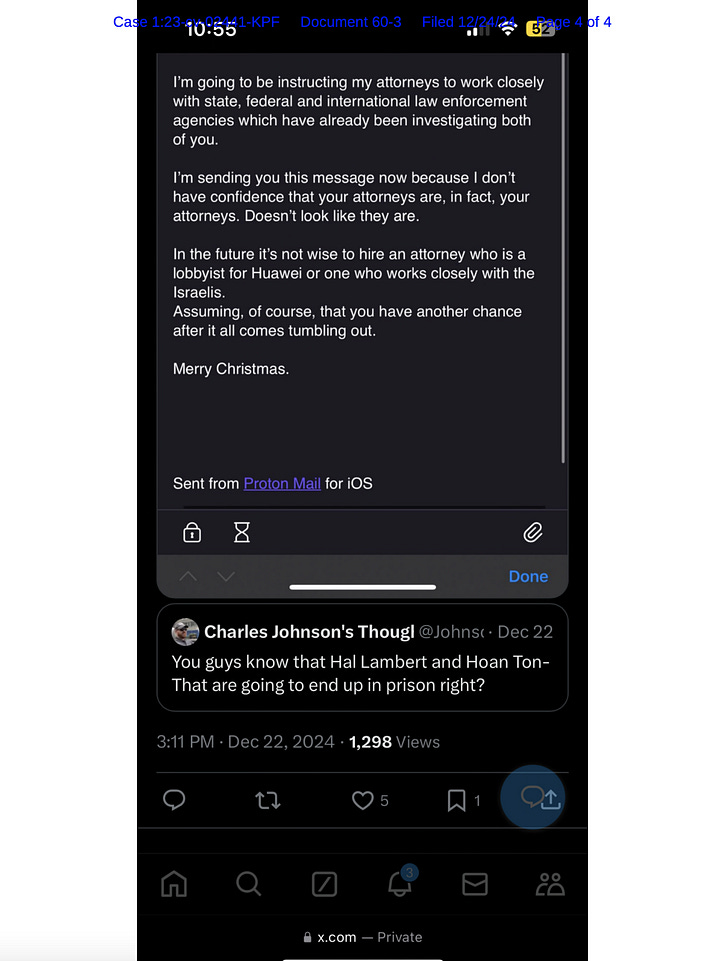

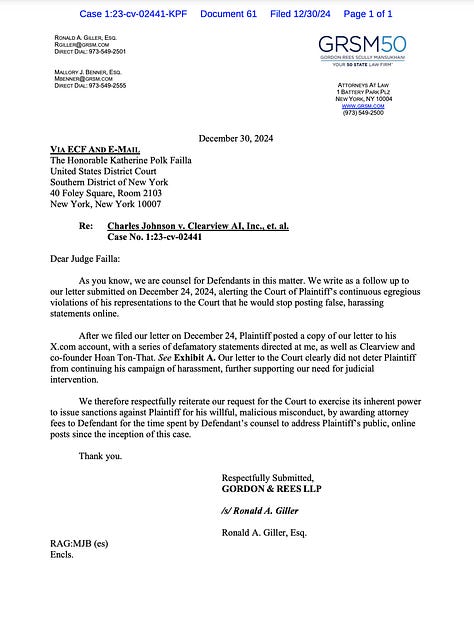

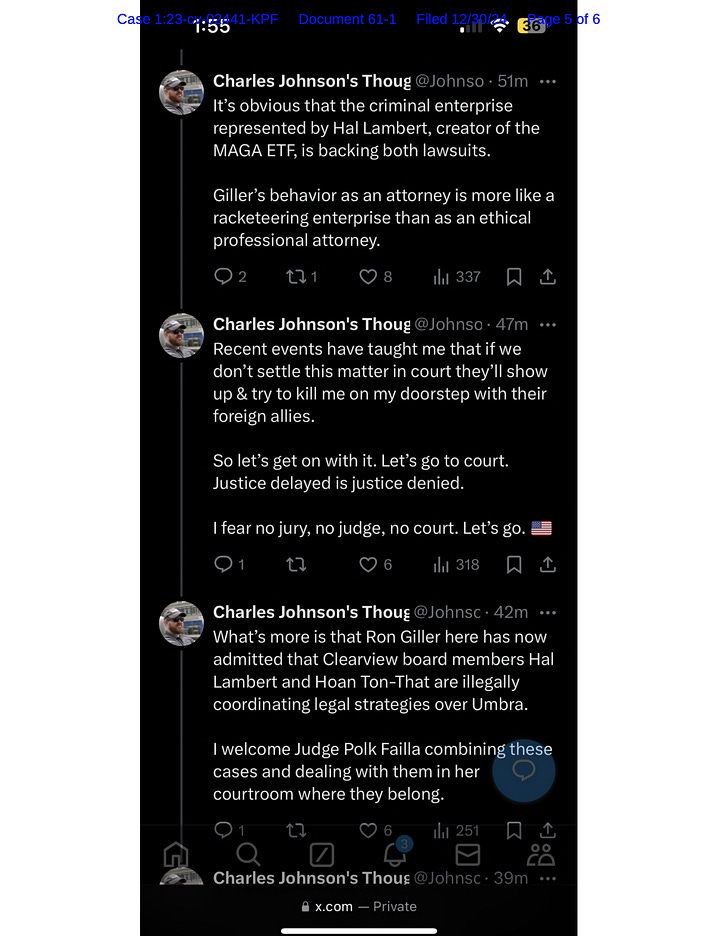

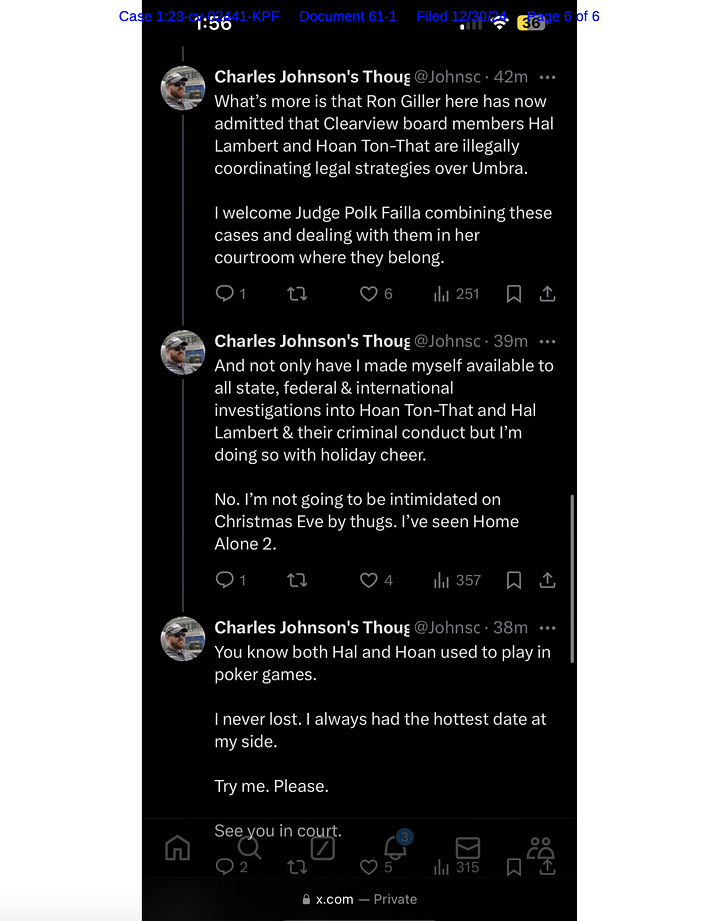

Charles hadn’t told me anything about the defense’s issues with his posts, which Ronald Giller, the defendants’ attorney, described as “harassing, highly offensive, and defamatory social media posts.” I started worrying about what Charles might have posted. The judge noted that Charles had been instructed to stop posting about the case but hadn’t complied. She questioned his attorney, Bernie Kleinman, about his ability to rein in his client. Kleinman stumbled through his response.

Giller requested the court order Charles to pay the defendants’ attorney fees, arguing that his posts were creating unnecessary work. He claimed Charles had made threatening posts, including antisemitic remarks, and expressed fears for his safety. Judge Failla wryly noted that Charles’ posts submitted as exhibits had minimal engagement.

Judge Failla questioned why Charles would call the defendants criminals and say they were going to jail. Charles replied, “Because they are!” The judge responded, “You know you’re under oath, right?” to which Charles replied, “That’s why I’m stating it for the record.”

Yesterday, I looked up the social media posts the defense submitted to the court as exhibits, and they were laughably tame.

Giller went on at length about how Charles’ posts made him feel he was in danger for being Jewish. His concern seemed genuine but childish, as his ingrained fear of religious persecution clouded his ability to assess the facts at hand. He also complained about Bernie Kleinman repeatedly misspelling his name in court documents.

Judge Failla declined to sanction Charles, but Charles agreed to stop publicly communicating about the case.

Part 2: The Matter of Discovery

The hearing then turned to discovery issues, but my lack of sleep caught up with me, and I started nodding off.

Part 3: Burying The Lead & Letting Go

Kleinman moved on to the next order of business and informed the court that Charles wanted to drop his claim against Clearview. Judge Failla was immediately taken aback; her mood shifted toward excitement as she remarked that the plaintiffs had “buried the lead.” She questioned Charles about why he would drop his claim, especially considering that Clearview hadn’t agreed to drop their counterclaim.

Charles choked up and explained that he had kept fighting for his daughter and ex-wife, who are shareholders, and out of a desire to secure their future. However, he now realized he had been deceived about the legitimacy of Clearview as a business, which left him extremely embarrassed. The case had dragged on for years, and Charles expressed grave concerns about the technology being used for malicious purposes; his fight began when he opposed providing Clearview to Israel so it could be used to target Palestinians.

He added that he no longer wanted to be affiliated with a criminal enterprise and stated for the record: “I have been in touch with federal authorities.”

Judge Failla: "Did you get in touch with federal authorities?

Charles Johnson: "No, they got in touch with me."

This impressed the judge, who seemed thrilled by the development. I wonder about her own concerns regarding the legality of Clearview’s business activities. While Judge Failla presides over civil court, she is a former prosecutor.

Judge Failla swiftly inquired with the defense to see if they could contact their clients right away to determine whether they would drop their counterclaim if Charles dropped his. Giller stumbled over his words, indicating that Hoan Ton-That might be unreachable and that they would need to consult Clearview’s board. Charles retorted that Ton-That could make a unilateral decision because he holds a controlling stake in the company.

Obviously pleased at the prospect of resolving the case, Judge Failla offered her availability over the next few business days, even suggesting reconvening later that day to move things forward.

As of this writing this case is ongoing.

Good Faith Debates About Surveillance

As Americans, we must consider how debates about free speech and privacy have been weaponized against us. Sophisticated AI and surveillance technologies demand good faith discussions about their role in everyday life—they aren’t going away.

The technological revolution of the past 25 years hasn’t necessarily improved our lives, while consolidating power among a handful of billionaire technocrats. Should we know the identity of everyone residing in the country? If identification is required to vote, shouldn’t minors need one to fly? Many vested interests resist solving the immigration crisis because it disrupts human and drug trafficking operations. Is mass documentation the answer to addressing an undocumented and exploited underclass in the U.S.?

Don’t ask Charles—he’s not allowed to talk about his case.